Executive Summary

Developing a Business Strategy concerns many people in business. This concern is understandable. Not only is some form of strategy required to align collective behaviour and achieve goals, but strategy development is difficult in a complex world, especially when there are contradictory meanings ascribed to strategy and its sibling tactics. In addition, there are many ways to do both.

Is there a way to reduce the confusion and anxiety? Fortunately, there is, and it’s called Emergent Business Strategy Development, or in the nomenclature of the day, perhaps we could call it Lean Business Strategy Development.

Lean business strategy development is essentially a specific instance of the Plan, Do, Check, Act (PDCA) development cycle applied to business strategy development and implementation. Lean business strategy development is by no means a panacea; it’s merely a pragmatic approach to a complex area of business.

Note: If you prefer, you can read the PDF version of this paper HERE.

Introduction

Does the thought of business strategy concern you? Is it the thought or admonition that you should have a business strategy and haven’t that does it? Is it that you don’t know how to develop a business strategy? Is it that you haven’t got a business strategy consultant (prophet) you can call on to create profits? Do you even know what a business strategy is?

The word strategy, and its close contextual sibling tactics, are among many words that are used, abused, and misused by those who apparently can’t be bothered to open a dictionary to check on the approved definitions. I know that language develops over time, but I am going full Don Quixote and actively resisting ignorance-based misuse. However, that’s for another time. The thrust behind this paper is to shed a little light on strategy and tactics, and in the process, try to remove some of the mystery, the confusion, and consequently the anxiety.

What are Strategy and Tactics?

Here are the most unambiguous dictionary definitions I could find (ignoring military references) for strategy and tactics:

Strategy – A plan of action intended to accomplish a specific goal. Wiktionary.org

Tactic – A manoeuvre, or action calculated to achieve some end. Wiktionary.org

Confused? You’re Not Alone

To support the suggestion that the mystery and confusion about strategy and tactics are not merely in your head, or mine for that matter, I present some findings and views regarding the use of those terms:

- “In the context of military and warfare, the concepts of strategy and tactics have an illustrious history. However, the adaptation of these concepts into some of the business disciplines including marketing has been haphazard and arbitrary.” (Sheth & Malhotra, 2010)[1]. The narrative in that source also describes how some authors use the terms and how others do the opposite.

- “The field of strategic management cannot afford to rely on a single definition of strategy, indeed the word has long been used implicitly in different ways even if it has traditionally been defined formally in only one.” (Mintzberg, 1987).

- ‘‘The point is that these sorts of distinctions can be arbitrary and misleading, that labels should not be used to imply that some issues are inevitably more important than others. … Thus there is good reason to drop the word ‘‘tactics’’ altogether and simply refer to issues as more or less ‘‘strategic,’’ in other words, more or less ‘‘important’’ in some context, whether as intended before acting or as realized after it.’’ (Mintzberg, 1987), emphasis added.

The last point, making a distinction by calling planning to do something strategy and the execution of that plan tactics becomes fraught. Is one possible without the other, and what do you call it when the distinction between them gets blurred, as when strategy development drifts into tactics? Perhaps it is more useful to think of strategy and tactics as existing at either end of a continuum, with strategy development as pure thinking at one end and tactics as pure doing at the other end.

Further to the above, “[t]he dirty little secret of the strategy industry is that it doesn’t have any theory of strategy creation. Whenever we come across a brilliantly successful strategy, we are all inclined to ask, “Was it luck, or was it foresight? Did these guys have this thing all figured out, or did they just stumble into success?” A key thing to remember is that truly innovative strategies are always, and I mean always, the result of lucky foresight. Foresight, however, doesn’t emerge in a sterile vacuum; it emerges in the fertile loam of experience, coincident trends, unexpected conversations, random musings, career detours, and unfulfilled aspirations.” (Hamel, 1997). It turns out that you and I didn’t miss that lecture, it simply didn’t exist.

So, where are we? People use the terms strategy and tactics in confusing and contradictory manners and there’s no underlying theory of strategy development. This knowledge is great news; at least we know the facts. These facts allow us to separate our obsession for prediction and control from the illusion of predictability and controllability, as well as from what is predictable and controllable. These facts also show us that the confusion in business and the literature is not in our imagination.

What is a Business Strategy?

Mintzberg’s later writings have refined, but not retracted his views above. In dropping the term tactics, he instead takes a more practical approach to what happens in the field, the office, or the factory as the case may be.

(Mintzberg, 1987) talks about the 5Ps of strategy, facets of what a business strategy is or can be:

- Plan – a consciously and purposefully developed intended course of action, made in advance of the actions.

- Ploy – a plan used to out-manoeuvre a rival.

- Pattern – the consistency of behaviour, whether that behaviour was planned prior or not.

- Position – where an organisation fits within its environment, its niche in the market.

- Perspective – the ingrained way the organisation as a whole perceives and reacts to the world.

Business strategy development, however it is accomplished, is in addition to the 5Ps above, a creative process. A creative process conducted by thoughtful people used to inspire aligned collective behaviour by all stakeholders to achieve some desired future outcome; there’s a great deal packed into that little word, strategy.

What Does A Business Strategy Contain?

Some of the key questions that business people need to answer are why us and why our solution(s)? At the root of the answer to these questions are differentiation and distinctiveness.

Differentiation

Differentiation is what makes your solution meaningfully different to and therefore better than your rivals’, at least that is, in the minds of customers.

The discussion in this section[2] does not ignore entirely material inputs such as wheat flour for a baker, or equipment such as aeroplanes for an airline. The challenge is that material and equipment inputs are not differentiators as rivals can easily purchase from the same suppliers.

If we can’t differentiate by input selection, then perhaps we can differentiate by Operational Effectiveness? Operational effectiveness is performing all activities such as creating, producing, selling, delivering, and servicing a solution better than rivals. Where better refers to the balance between the minimisation of the costs of the solution’s input parameters while at the same time maximising the output parameters (benefits and therefore value) that customers care about.

However, operational effectiveness in itself is not the goal; it is the minimum performance you must achieve to remain in the game, in what we can readily observe is a very competitive business environment. Along with inputs, operational effectiveness is also easily copied because businesses can and do readily benchmark each other and therefore, any competitive advantages are not sustained for long.

So what remains if excellence in material and equipment selection as well as operational excellence are not differentiators, or won’t stay so for long? There are three principles to strategic positioning, that in addition to the above if followed, can assist with achieving sustainable differentiation:

- Create a unique and valuable market position where you perform different activities from rivals, or you perform similar activities in different ways. Ultimately what makes a business and its solution(s) different from rivals’ is the aggregation of the multitude of activities that form the inputs to the solution. For example, cost advantage is gained by performing activities more efficiently than rivals, and differentiation is increased by a different choice of activities as well as how they are performed.

- Make trade-offs on which market and market segment to compete in. A business has to decide what it is going to do and what it is not going to do. A business can’t easily and profitably be all things to all people; some activities and market positions are incompatible, such as attempting to be both a low-price volume supplier as well as a low-volume premium supplier. Trade-offs are choices about which niche to supply and where to concentrate resources for maximum effect.

- Create ‘fit’ amongst the business’s activities and therefore stakeholders. Fit refers to all of the business’s activities working together as an integrated whole; doing many things well, not just a few. When a business’s activities mutually reinforce each other, the whole in effect becomes greater than the sum of the non-integrated parts, a result that rivals cannot easily imitate.

(An exemplar for differentiation in general and these three principles, in particular, is the often referenced Southwest Airlines.)

However, apart from protections such as patents, trademarks, copyrights, intellectual property, and exclusive access to scarce resources, there is little to stop rivals from matching or bettering your solution(s), and thus erasing your differentiation. What does remain is making solutions distinctive, such as with a brand.

Distinctiveness

The challenge with all of the factors of differentiation above such as inputs, equipment, operational excellence, position, trade-offs, and fit, is that they can all, perhaps with considerable effort and expense, be copied or matched. As Byron Sharp wrote, “In spite of nearly every textbook telling marketers to strive for differentiation, real-world competition is largely about competitive matching rather than avoiding competitors by delivering differences.” (Sharp, 2014)[3].

What Sharp explains is that all of the factors of differentiation previously discussed are necessary but not sufficient in themselves. In the increasingly crowded and complex marketing landscape, Sharp argues that your business and the solutions that you provide need to be distinctive.

The way that a business and its solutions become distinctive is to develop an effective[4] brand with brand assets such as brand name, logo, colours, labelling and packaging, taglines, and symbols or characters.

There isn’t space in this paper to perform a deep dive into brands and branding, but we can nonetheless dip our toes into the evidence-based marketing pond.

What is a Brand?

To understand what a brand is in the context of business, here are some definitions:

Byron Sharp:

A service or product identified by a distinctive and individual name or logo that distinguishes the offerings of one company from those sold by their competitors. ‘Brand’ has three varied meanings, all of them correct:

- A named product or service.

- A trademark.

- Brand equity. (Sharp, 2017).

International Encyclopedia of Marketing:

[A] brand represents a promise of salient benefits to a set of target consumers. (Sheth & Malhotra, 2010).

Tom Blackett:

[Brand] has always meant, in its passive form, the object by which an impression is formed, and in its active form the process of forming this impression. (Clifton & Simmons, 2003).

In a sense then, a brand is effectively a promise that expectations, as previously established, will be delivered.

What is Branding?

The purpose of marketing is to develop, promote, and maintain your brand(s). For this, you will need to develop a Marketing Strategy.

Briefly, your Marketing Strategy will make your branded solution(s), or more simply your brand(s), available to prospective customers, where availability refers to both:

- Mental availability – the number of associations a buyer has about the brand, the strength of those associations, and the relevance of the associations to the buying context.

- Physical availability – making the brand as easy to find and buy as possible. (Sharp, 2014).

Business Strategy Development

In this section, we discuss first how strategy development is traditionally (thought to be) developed, and then we move onto a more practical strategy development strategy.

Traditional Business Strategy Development

Developing a business strategy can be achieved with the aid of models, by say conducting a Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis, and working with what you unearth. You can also use Boston Consulting Group’s (BCG) Growth-Share Matrix, to name a few. But trying to fit you and your business into some (perhaps trite and) generic matrix is only part of the story. Models assist by recommending an order and structure to apply to the thinking process. But models are not a substitute for thinking, and neither should using models devolve into (an annual) ritual, as in a rain dance, praying for a better future. Still, as valuable as models are, George Box cautioned, “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” And if a model by chance does happen to be a perfect fit, then it probably means that the model isn’t as sophisticated as you need it to be. You’re also likely to end up with an identical strategy to some other business(es), which will defeat the purpose of your attempting to develop a differentiated business strategy in the first place.

Another way to develop a business strategy is to use consultants who are supposed experts in your area of interest. However, there are well-documented concerns about using consultants, ranging from them delivering expensive sterile generic reports, to getting little buy-in from those on which the strategy will be imposed, and to not receiving implementation plans.

You can also develop a business strategy with your team. Although there are risks to not engaging outsiders such as consultants for different points of view, the experiences of employees and other stakeholders should not be dismissed out of hand. The benefits of in-house strategy development are access to local knowledge and experience, and you potentially get buy-in from the co-development. You also, in theory, have the stakeholders on-site and onboard to challenge both the plans and the implementation as facts come to light, and both can be adjusted as required.

There is considerable risk in the preceding discussion that people are relying on forecasting, and what we know about predicting the future, such as the weather and business trends is that they are exceedingly difficult to predict with accuracy.

Emergent Business Strategy Development

Is there a way to develop a business strategy that does not depend too heavily on you, your team, or prophets predicting the future? (Mintzberg, 1987. P13) thinks so, by distinguishing “deliberate strategies, where intentions that existed previously [are] realized, from emergent strategies, where patterns [develop] in the absence of intentions, or despite them (which went unrealized).”

Is falling back on emergent business strategies simply admitting that you lack the imagination, creativity, skill, experience, and intelligence to do your job, to develop a strategy, any strategy? Is it just making things up as you go along? Not necessarily. To accept that we can’t reliably predict the future, and that valid strategies can emerge, is to have a firm grip on and understanding of reality, on what is practically possible and what happens daily. Does this mean that we should abandon or refrain from forecasting and planning? No, it simply means accepting that no plan survives intact the first contact with reality[5]. But planning, with its roots in the past, is an abstraction of current reality and a forecast of a future, and it is still required. You can’t expect to be successful remaining ignorant of what was, what is, or what could be.

Business strategies are like maps, in that the right map can orient, guide, and inspire people. With such maps, the outcomes of the first forays into the dynamic and complex real-world can be compared to what was predicted and intended, and appropriate course corrections made, and the strategy updated.

The Journey of a Thousand Iterations …

So, if crystal ball gazing has its limits, and you’re at a loss as to what to do, where do you start?

“The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.” Lao Tzu.

Based on your hypotheses (assumptions and guesses), what you know, whom you know, the resources you have, and where you are, do something, take a step. Take a step, see what happens, learn from what happens, take the lessons on board, and then take another step. And then repeat with another step.

This advice is not suggesting random and or reckless behaviour. It is instead recommending that you perform an opportunity and risk analysis and that based on all your resources, context, starting position, and as well as your risk tolerance, that you make a start, that you take a step.

This iterative approach has many variants, such as the Plan, Do, Check, Act (PDCA) cycle, and the Build, Measure, Learn Loop.

A similar approach comes from, a perhaps more abstract field, complexity science, where to get things done you repeatedly:

- Probe – the environment by trying something.

- Sense – and analyse the outcome of the probe.

- Respond – to what you have learned.

The PDCA-type approach to business strategy development is nothing new. It has been called logical incrementalism, a “management philosophy which states that strategies do not come into existence based on a one-time decision but rather, [they exist] through making small decisions that [are] evaluated periodically. These small decisions are not made randomly but logically through experimentation and learning.”[6] And, “[o]rganizations employ the process of logical incrementalism because it is more practical and responsive to the complexity and uncertainty inherent in strategic challenges. Logical incrementalism adapts the pragmatic and functional elements of traditional, formal analytical processes, as well as processes that recognize and manage the power and psychological shifts inherent in strategic change.” (Camillus, 2016).

To wrap up this subsection, (Hamel, 1997) wrote, “[t]he more experimentation, the faster a company can understand precisely which strategies are likely to work. The goal is not to develop “perfect” strategies, but to develop strategies that take us in the right direction, and then progressively refine them through rapid experimentation and adjustment.”

Today the principles of logical incrementalism are more commonly known as Lean, and the principles of Lean are applied to a wide variety of fields, such as manufacturing and software development. For us concerned with business strategy development, maybe we could call what we are doing Lean Business Strategy Development.

So What Are You To Do?

For a start, if you were concerned that you couldn’t hatch a fully formed and realistic business strategy in a single bound, then hopefully, you can relax a little; it just doesn’t happen. If you were practising emergent business strategy development, even if you didn’t call it that, then hopefully you can draw some comfort and support from the preceding discussion; that does happen.

But what if you’re just beginning your journey?

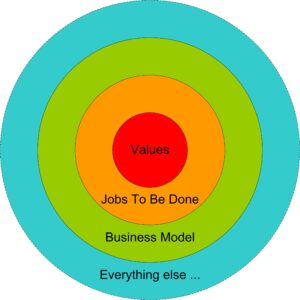

To apply a bit of structure to our thinking, imagine the structure of an onion as representing the structure of a business, with the innermost layers towards the core representing increasingly distilled fundamental and foundational business factors, and in the other direction, the succeeding outer layers representing successive detail heaped on top of details. The onion model, as with most models isn’t perfect, as in reality, details don’t confine themselves to their assigned layers; details care little about our expectations. In addition, as sophisticated as the onion model may be, it’s only 3-dimensional, and with our real-world complexity, details tend to have far many more dimensions, or interweaved details affecting other details in other layers, than our model permits. However, all that said, the layered onion model of business strategy is helpful in being able to visualise that at its core, lies the genesis of everything else.

Nearing the core of a successful business is a viable and sustainable Business Model, where:

- Viable – means that customers buy your solution to fulfil their Job To Be Done (needs).

- Sustainable – there are sufficient prospective customers to:

- To achieve your profit objectives so that you can start and then stay in business.

- Achieve your growth objectives.

- Enable you to develop a strategy for Enduring transient competitive advantage

Nearer the core, we have customer Jobs To Be Done, as in, see a need, fill the need. Without a job to be done, no product, or as I prefer, solutions, can be sold. As Steve Blank said, “build it and they will buy is not a strategy, it is a prayer,” “you cannot create a market or customer demand where there isn’t customer interest.” And that interest begins with a job to be done.

Perhaps at the core are our values[7]. With values (and empathy), we have a sense of and a framework for what is interesting and important to us as well as to others. With values, we can recognise jobs that need doing. And what we find interesting and important drives our enthusiasm (passion), to get out of bed and do things.

The onion model is usefully applicable to business strategy development, especially for the first three layers; after that, the model probably depends on your context, where it probably becomes an onion-mesh hybrid.

- Values – we all have some, regardless of whether or not they are ultimately useful to us.

- Jobs To Be Done – you can’t sell solutions that people don’t want.

- Business Model – the viable, sustainable, and perhaps perpetual value exchange machine (money go around).

- Everything else that enables, supports, and perpetuates the Business Model.

Creating Your Business Strategy

The onion model of business is a useful abstraction representing nested levels of dependencies. Whether the dependencies are nested, hierarchical, or some other structure, is not the point being made. The point is that your prime business strategy will have sub-strategies, even if only for the purpose of dividing the overall strategy into smaller more manageable sub-strategies (tasks). Those sub-strategies will, in turn, have their sub-strategies, and the whole, being a set of dependencies will, therefore, have a structure.

In project management parlance, you have a project (prime-strategy) consisting of sub-projects (sub-strategies). And for as long as it is useful, each sub-project can recursively have its own set of sub-projects, ad infinitum, with the whole becoming a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). And before we lose sight of why we’re discussing all of this, the whole being aimed at achieving the goals of the project, or in our case, our business.

For our purposes here, it is assumed that you have values (and empathy), and since it is not our place here to analyse those, the primary objective and the core of developing a Business Strategy is therefore, identifying a Job To Be Done.

Business Strategy Development Outline:

- The overall/prime strategy is to develop a viable and sustainable Business Model.

- To achieve (1), the sub-strategy is to use The 1-Page Business Model, which provides the seven factors for a successful Business Model.

- For each of the seven factors for success in The 1-Page Business Model, where the first factor is identifying a Job To Be Done, the sub-strategy is to develop emergent strategies to satisfy each factor. Such sub-strategies could include strategies for financing, purchasing, manufacturing, marketing, scaling, and enduring transient competitive advantage.

- In support of (3), the sub-strategy is to use the article Identifying A Job To Be Done as an introduction to finding a job.

- In support of all the above, the sub-strategy is to use the book Starting a Business With Facts, Not Faith. (Davies, 2019).

- For all the above, the strategy is to plan as far as you can, try something, find out what happened, learn from the results, and then repeat. Or, if the situation has become futile, pivot or abandon.

Final Words

The objective of providing this paper was not to distress anyone or to frighten you into my business. The aim was to provide the naked truth as I understand it. There is too much at stake in business to rely on belief, wishful thinking, and ultimately gambling. If in the end, I have deterred anyone from gambling away their resources on a predictably futile exercise, then I have done my job. Such people may not shower me with gratitude by having shattered their dreams, illusions, or delusions, but hopefully, they will still have most of their resources intact.

I hope that this shallow dive into business strategy development has been useful to you; there is a limit to how much one can cover ‘in a few pages’ when many other authors have devoted hundreds of pages each.

If you need something clarified or need any help, then please reach out for a no-obligation ‘chat.’ I won’t chase, spam, or otherwise harass you. It has been shown that when people need help, they have to reach out for it; shovelling advice down your throat does not work.

Footnotes

[1] Chapter Marketing Strategy, Rajan Varadarajan, P156.

[2] This section is based on a paper by Michael E. Porter, What Is Strategy? Harvard Business Review, November-December 1996.

[3] Chapter 8: Differentiation Versus Distinctiveness.

[4] Effective – meaning a positive return on marketing investment is realised.

[5] Paraphrasing Helmuth von Moltke, Wikiquote, accessed 23 July 2020.

[6] businessdictionary.com

[7] It would make for an interesting discussion about whether or not values are the core, or if there is something more fundamental. I know however, as I write about in the post on Values, Vision, Purpose, Strategy, and Mission, that values are not something that you sprinkle on your business as an act of political correctness and or fashion compliance after you have created it. But that discussion can wait for another day.

Bibliography

Camillus, J. C. (2016). Logical Incrementalism. Palgrave.

Clifton, R., & Simmons, J. (2003). Brands and Branding. London: The Economist.

Davies, G. C. (2019). Starting a Business With Facts, Not Faith (2nd ed.). Auckland, New Zealand: Don’t Think, Check! Limited.

Hamel, G. (1997, June 23). Killer Strategies That Make Shareholders Rich. Fortune Magazine.

Mintzberg, H. (1987). The Strategy Concept I: Five Ps For Strategy. California Management Review, 11-24.

Sharp, B. (2014). How Brands Grow: What Marketers Don’t Know. Oxford University Press.

Sharp, B. (2017). Marketing: Theory, Evidence, Practice 2nd Edition. (2nd ed.). Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Oxford University Press.

Sheth, J. N., & Malhotra, N. K. (2010). Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing. Wiley.