Introduction

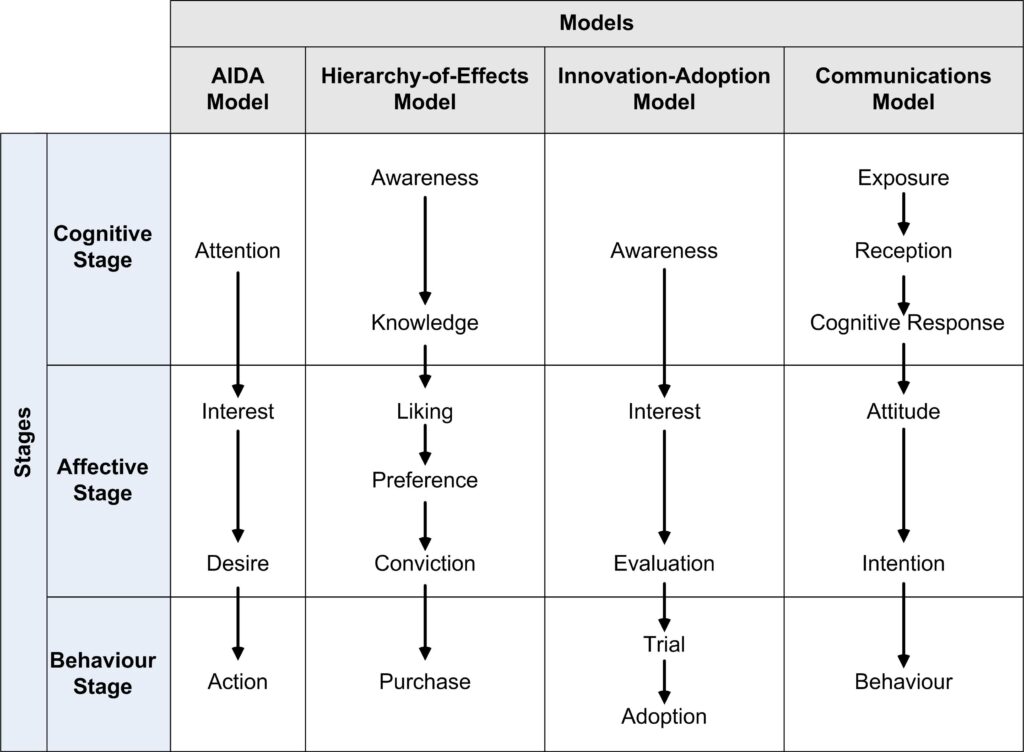

Consumers of products[a] typically progress through a series of stages, a Customer Response Hierarchy, regarding their purchase or non-purchase of products. Or so economists and others interested in modelling such things would like to think.

[a] In this post, product is the generic term for “the result of an action or process.” en.OxfordDictionaries.com. This is as opposed to the preferred practice at DTC of using the collective term solutions.

Creating a model of consumer behaviours or responses is useful to help understand the journey that consumers undertake to possibly become customers. With a model, we can develop a common frame of reference, a common terminology, a common understanding, and perhaps we can even have meaningful discussions.

A number of models, known as hierarchy of effects models have been developed. The models suggest that consumers move through a series of steps or stages when making purchase decisions.

The diagram below presents some of the better-known models.

Adapted from: Fig. 19.2, Marketing Management 15e, Philip Kotler, Kevin Lane Keller.

Measurement Criteria

Essential measurement criteria in any model are:

- How many prospects are entering a stage?

- Are they entering from a/the previous stage?

- Is this their first appearance?

- Why do customers not make it to the next stage?

- What is the cost of customer acquisition, the cost of converting a prospect into a customer? Is the acquisition cost less than or greater than the lifetime value of the customer?

The Hierarchy-of-Effects Model

A brief description of the Hierarchy-of-Effects Model above is:

- Awareness – are prospects aware of the solution?

- Knowledge – how much knowledge do prospects have about the solution?

- Liking – given that prospects know of the solution do they like it?

- Preference – do prospects prefer your solution over others?

- Conviction – do prospects develop a conviction to purchase your solution?

- Purchase – do prospects with conviction finally make a purchase?

Discussion

Dave McClure of 500 Startups has also developed what he calls Pirate Metrics, which you can access via this link,[1] in a similar vein to the above, which is particularly suitable for companies primarily selling on the internet:

- Acquisition – How do prospective customers find out about you and visit your website or physical store. Are you counting these people?

- Activation – How many prospects are either staying on your website for a defined minimum time or how many of your physical store visitors make enquiries and handle the goods?

- Retention – For website visitors, retention is a measure of prospects making return visits. This metric will apply to a physical store when prospects take time to make their minds up and or return for more evaluation, but it won’t be applicable if they purchase on the first visit. Retention can also mean that prospects continue to pay their annual license fee or they continue to buy your coffees say.

- Revenue – How do you make your money? When do you get paid? Upfront per item, free first month, upfront monthly, upfront annually?

- Referral – Does anybody refer your solution to others?

You may have to adapt or create a response hierarchy model that best suits your context and solution; another example model similar to the above is the 5 A’s Framework[2]. But regardless of the model you use, you will need to collect metrics. But merely collecting metrics is not enough; once obtained, you must analyse the data and use that information to inform your response actions.

Every channel (see below), a path to reach customers, will have a response hierarchy.

Channels

Channels are the different paths to reach, communicate with users and customers, and to sell to customers, where each path has a customer response hierarchy (see above). Different solutions lend themselves to some channels but not others, for example, a freemium channel for bulldozer sales is most likely a non-starter, whereas freemium channels seem to work well for mobile phone applications.

The goal of start-up businesses is not to scale but to learn. Any channel that gets your solution in front of prospects is excellent, but you need to realise that the path to early adopters may not be the same path to mainstream customers.

Ash, in Running Lean, discusses various channels:

- Freer (freemium) versus paid – All channels have a cost associated with them, some may be more effective and economical than others, but they all have costs.

- Inbound versus outbound – inbound channels pull prospects towards you with Search Engine Optimisation[3], blogs, and whitepapers, whereas outbound channels push messages towards prospects with Search Engine Marketing[4], advertising, tradeshows, and cold calling.

- Direct versus automated – automated selling lends itself to scalability, but first, you need to create traction by selling manually. Beware of premature optimisation before you have made any sales or achieved significant sales volume.

- Direct versus indirect – direct selling refers to you selling your solution as opposed to indirect selling which refers to getting others to sell your solution for you. You first need to sell your solution and generate traction for indirect selling to work.

- Retention before referral – before you can hope for referrals, you first need to have a remarkable solution, then and only then can you hope for customers, hope to retain those customers, and then again hope for those customers to advocate, to in effect, sell your solution for you.

[1] https://www.dontthinkcheck.co.nz/blog/sab-wfnf-3rd-edition-resources/

[2] https://www.dontthinkcheck.co.nz/glossary/five-as-framework/

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Search_engine_optimization